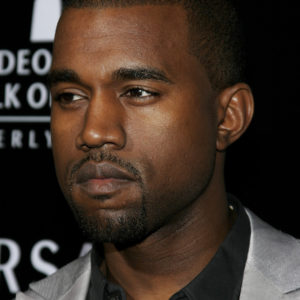

Ye (formerly known as Kanye West) was recently embroiled in a series of self-created controversies that severed and strained business relationships with partners such as Balenciaga and Adidas.

At the time many thought Ye was publicly imploding, he told Rolling Stone something that fell under the radar in such a tumultuous Ye news week — that he plans to create his own Metaverse.

In September, Ye filed trademark applications for the names “Yecosystem” and “Yeezyverse.” The trademarks will include protections for drinks and branded food items. Stores bearing Ye’s name, something he is working toward IRL (in real life, for the uninitiated), would exist in his Metaverse.

To understand how this might work, we need a refresher on what the Metaverse is and isn’t.

The Metaverse is a virtual reality that can be used for business, education and social networking. Proponents want us to imagine if everything we did online was integrated into a single world — we could meet people from all over the world in real-time and explore new places that have been created by others.

Another way to look at the Metaverse is by comparing it to our current physical reality: If we’re in a shared physical space — say, a café or, in this case, a virtual storefront branded and run by Ye — we can each see the same things in front of us but from our own perspective. In the same way, users will have access to their own unique version of the Metaverse, depending on where they are and what devices they’re using.

What Ye is trying to do aligns well with Mark Zuckerberg’s vision of the Metaverse. Zuckerberg believes the Metaverse will afford us as consumers to get these new, special experiences. If Zuckerberg’s vision was to have Facebook/Meta facilitate its users interacting with each other at all times using whatever medium they find most convenient, Ye’s mark on the Metaverse is to have as many of those interactions as possible have a touchpoint to his own brand.

Yet not everything in the Metaverse is going to be net new. A lot of what we see there will be a virtual version of what we already have, which should raise some yellow flags for us.

Krenar Camili, a Passaic County, N.J., lawyer, reminds us that these new spaces don’t erase things already built.

“When it comes to creating things in a new space, such as the Metaverse or, as Ye wants to do, the ‘Yecosystem,’ you’re still bound by legal structures that already exist. So if someone goes to the Metaverse and were to simply recreate the Adidas brand, for example, that violates existing intellectual property rules here in the real world.”

We must also remember that everything on the Metaverse comes with some built-in vulnerability.

It will be easy for companies to track our movements through their software or hardware as we play games, watch movies, shop, or just hang out within the Metaverse generally or any given segment of it. This means that companies may have access to information about how much time you spend looking at specific ads and whether or not those ads influenced any purchases on your part.

The lesson here is that the less we trust people and brands in our world, we should trust them exponentially less in the Metaverse. This lesson is one Ye should pay close attention to. If his actions excessively damage his brand in our physical world, there is no clean start in the virtual world.