The business of competition in sports is exploding beyond athletes, with most Americans now enjoying a range of options from gambling sites like DraftKings to prediction markets like Kalshi. As the industry booms, state gambling regulators are trying to assert authority over all of it, including prediction markets, in a direct threat to the global financial markets.

The matter is now being contested in courts across the U.S. But the law is clear, thanks to reforms we helped shape after the 2008 financial crisis: Prediction markets should have to answer to their federal regulator, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, and nobody else.

Our strong belief in this principle is why we signed on to an amicus brief supporting Kalshi in its legal fight against the New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement. The case, now before the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals, has profound implications: If Kalshi loses, states could have carte blanche to prohibit any futures or other derivatives contract they object to, potentially throwing the $730 trillion global derivatives market into chaos.

Such an outcome would also undermine the post-crisis changes we worked on in Congress. If the states are successful in unwinding that authority, they will invite a global disaster that dwarfs the wreckage of the last crisis.

To understand where we are, it’s important to know how we got here. Congress created the CFTC a half-century ago to replace a messy state-level patchwork that failed to police cheating, fraud and manipulation in futures markets. It instead granted the CFTC exclusive jurisdiction over futures trading in all commodities. Wielding sole and sweeping power, the CFTC fulfilled its promise: Futures markets matured and flourished.

Thirty-five years later, those of us serving in Congress in the aftermath of the crisis and tasked with carving its lessons into law understood the imperative to expand the CFTC’s authority beyond futures to additional types of derivatives. The Dodd-Frank Act that rewrote Wall Street rules addressed the damage wrought by these unregulated derivatives by extending the CFTC’s exclusive control over them. That increased preemption is now coupled with another Dodd-Frank Act provision directly covering trading on prediction markets. Indeed, it spells out that such trading is allowed on markets licensed and regulated under the CFTC’s exclusive jurisdiction over futures and other derivatives, unless the agency proactively finds a contract is “contrary to the public interest,” such as speculation related to terrorism or assassination.

This debate may seem like a trivial regulatory turf war over a startup industry. But we have learned the hard way what happens when the CFTC is absent from these markets. The agency guarantees the smooth functioning of derivatives, a vast marketplace that underpins the global economy. Allowing states to start chipping away at its power would sow investor doubt, potentially unraveling U.S. primacy in the marketplace and sparking capital flight from our commodities markets. The market disruption that would follow is a summer sequel nobody wants to see.

So far, the courts that have examined state gambling regulators’ arguments have reached the right conclusion. In New Jersey, for example, a federal judge in April intervened on behalf of the prediction market, preserving its ability to offer sports-related trading. The judge pointed out that Kalshi’s federal regulation by the CFTC preempts the state regulator’s attempt to step in, a principle guaranteed by the Constitution.

New Jersey appealed that ruling, setting up a clash in the 3rd Circuit, which will hear arguments in the coming weeks. To ensure the CFTC’s authority is preserved, and along with it the hard-won wisdom of the global financial crisis, judges must order states to back down.

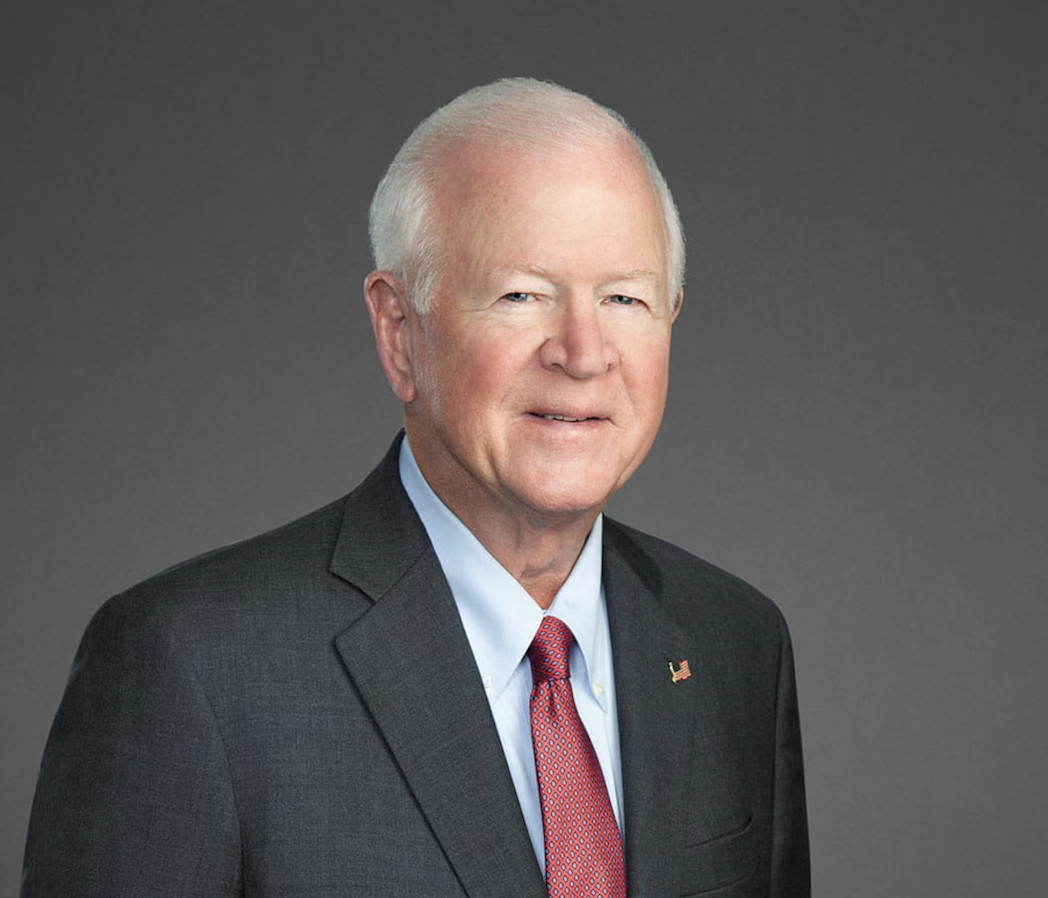

Former U.S. Sens. Chambliss and Baucus helped shape the Dodd-Frank Act as members of the Senate Agriculture Committee in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.