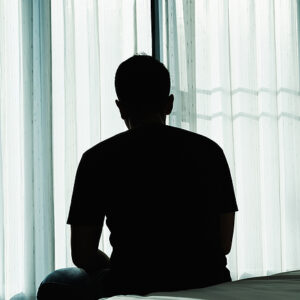

The nation, I read, is in the grip of a loneliness epidemic.

This has all been made worse, one suspects, by the effects of the pandemic-induced lifestyle changes — consequences of the forced isolation that changed social and work practices in ways that haven’t changed back.

Other changes have been coming slowly over the decades, but all add to the lonely life. The way of life has had a trajectory for those who live alone, which has increased the possibility of loneliness.

We isolate ourselves in ways that are new or only decades old. We drive alone. We live in a house or apartment, if single, alone. We work alone in that dwelling, facing a computer or watching a movie on television alone.

I call this the box culture: We drive in a box, live in a box, and, as likely as not, stare into a box as we work.

Changing work patterns are probably a critical part of the structural loneliness that is now rampant. Even if one doesn’t work at home, we work differently. We used to make contacts, and essentially new friends, by doing business on the telephone. Now we shoot off an email and maybe, if it can’t be avoided, make an appointment to make a video call with several people.

We have wrung out all spontaneity. Making friends is a kind of spontaneous combustion. You might as well be doing business with AI for all the lack of warmth or humor in today’s work interactions.

Then there are work friends. For most of us, it was at work or through work that we made our friends — that is, if they weren’t carryovers from school or college.

People who work together and play together fall in love, sometimes get married, and sometimes meet a friend who undoes a marriage. There is a lot of sex at places of work, although companies might deny it. Note the number of CEOs who marry their assistants.

Another feature of the loneliness structure is that pub life is in decline. The local tavern, even for non-drinkers, was part of the way we lived, and drinking isn’t as pervasive as it once was.

Time was when after work or wishing to see a friend, you went for drinks. People gave drinks parties at noon on weekends: no food, just a convivial glass. That isn’t extinct, but it isn’t what it used to be.

Drinking oils society’s wheels — too much, and the wheels come off. Go sit at the bar, and someone will talk to you. There is camaraderie in a saloon.

Entertaining has become more formal. Blame all those cooking shows on television. People don’t have friends over for a hamburger anymore. No. They have to have Steak Diane and a soufflé — a meal with the stamp of Julia Child on it. Result: less dropping in on friends, more isolation.

Of course, there are those who are lonely because of bereavement, sickness, old age and family abandonment. But those things have always been with us. They really suffer loneliness, feel the terrible blanket of isolation.

For those who have decided it is too strenuous to go to the office, that the phone is for messaging, that home loneliness is inevitable because we can’t cook or are ashamed of our homes, join something: a church, a theater group, a book club or do volunteer work.

Much of loneliness, from what I can divine, is a product of how we live now. We sit in our boxes inadvertently avoiding others. Television isn’t friendship, drinking alone isn’t companionship. Go shopping in a store, go to church, go to the pub, work in the food bank, join a book club. As the old AT&T advertisement used to say, “Reach out and touch someone.”

No one can predict how or where great friends or great loves will be found, but certainly not staring at a computer.

Several of my greatest friendships are a result of people who have taken violent exception to something I have written and wanted to meet up to berate me. The facts were wrong. I was evil, I met them to take my medicine, as it were, and parted knowing a new friend.

The Surgeon General has raised the issue of loneliness. He would be advised to tell people to look at lifestyle. Does it have loneliness baked in?