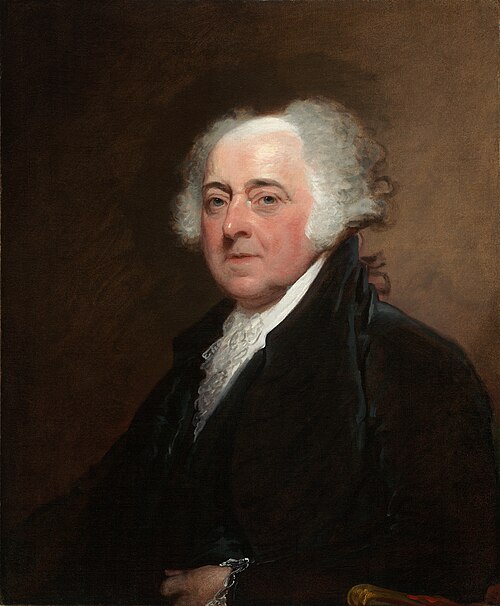

John Adams is a giant among American Founders, yet something is missing: a memorial in the nation’s capital.

That could be changing, not just for the second president of the United States but for the entire Adams family.

There is bipartisan support in Congress to provide up to $50 million, to be backed by private matching funds, for a memorial to be completed by 2032.

So why did it take this long for an Adams memorial?

“John Adams was caught between two enormous figures,” said Jackie Gingrich Cushman, president of the Adams Memorial Foundation.

He was overshadowed by his predecessor, George Washington, and lost an election to Thomas Jefferson.

Then there was the sixth president of the United States.

Cushman called John Quincy Adams “among the most overlooked” statesmen in American history.

The daughter of former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, Cushman said, “The memorial will reflect that America is so strong because of families.”

Cushman testified before the House Natural Resources Committee in July, advocating for the project and the enabling legislation, the “Great American Heroes Act,” introduced by Rep. John Moolenaar (R-Mich.).

This tribute would include a library in a garden and honor not just two presidents but other family members, including the profoundly influential Abigail and later generations like Charles and Henry.

“This park-like setting, graced with mature trees, would be a perfect place for this memorial — composed of a library in a garden — that is being contemplated. The site’s adjacency to the White House would also help the story of John Adams and the creation of the nation’s capital city come alive,” Cushman told the House committee. “On Nov. 1, 1800, John Adams became the first president to live in the White House by moving in while it was still under construction.”

Further, Cushman noted it would be the most prominent memorial dedicated to a woman in Washington. The second first lady, Abigail Adams, was known for her counsel to her husband, her independent spirit, and her role as a key influencer in the formation of the nation.

The need for such a memorial is not merely to acknowledge past greatness, but to confront a fundamental, and often uncomfortable, truth about the American experiment: it was never inevitable, and its success was forged in political strife and human fallibility. All of the Founders knew they faced treason charges if they lost.

While he lived in the shadow of the man he served under as the nation’s first vice president, it’s worth noting that John Adams nominated George Washington to be commander in chief of the Army during the Revolution, a testament to his clear-eyed judgment.

His legacy is one of profound and at times contradictory contributions. He could be characterized as both hawkish and prudent on the national security front. He established a strong Navy and, against the grain of his own Federalist Party, steered the young nation away from an unwise war with France.

Yet his signature on the Alien and Sedition Acts stands as a stain on his record, and a challenging moment for press freedom in the young country.

John Quincy Adams came to the presidency after a highly controversial election in 1824, unfairly marked by accusations of a “corrupt bargain.” His single term in the White House was a difficult one, but his true legacy was built in his post-presidency. As a member of the House of Representatives, he became a heroic and tireless opponent of slavery and proved that a leader’s greatest influence is not always tied to their time in the presidency but to their courage in the face of injustice.

Cushman notes the younger Adams briefly served in the House at the same time as U.S. Rep. Abraham Lincoln.

The memorial could be located near the White House, which would be particularly poignant, bringing to life the story of John Adams as the first president to inhabit the unfinished executive mansion.

His words to Abigail — “I pray Heaven to bestow the best of blessings on this house and on all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise men ever rule under this roof” — remain in the State Dining Room.

Today’s political climate is often described as unprecedentedly polarized. But a look at the lives of the Adams family reveals that the messy, fraught nature of our politics is as old as the republic itself.

In their struggles with a hostile press, disputed elections, and the fundamental question of who we are as a nation, they provide a powerful mirror for our own era.

“As Founders, diplomats, and as the second and sixth presidents of the United States, the Adams family dedicated their lives to our country,” Moolenaar, the lead sponsor, said earlier this year. “This historic family was instrumental in the early success of our nation and embodied core American values.”