40 Wall Street is much in the news lately.

The historic 72-story office tower, once the tallest building in the world, sits directly across from the New York Stock Exchange in the heart of the financial district. Originally the Manhattan Company Building, it’s now called the Trump Building. It’s been identified as one of several properties New York Attorney General Letitia James threatened to seize from former president Donald J. Trump in the New York v. Trump civil fraud case.

Interestingly, this isn’t the first time 40 Wall Street has been involved in complicated financial dealings with presidential ramifications.

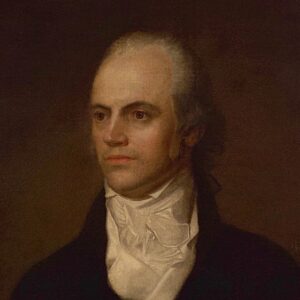

Those of you familiar with the multiple Tony Award-winning musical “Hamilton” will remember that Alexander Hamilton, America’s first secretary of the treasury (under President George Washington), died in 1804 in a duel with Vice President Aaron Burr. Less well-known (hat tip to Jay Larson) is the fact that Burr was the founder of the Manhattan Company, 40 Wall Street’s previous longtime owner.

Burr created the company in 1799 ostensibly to provide Manhattan residents with clean drinking water. The real purpose of the company, however, was to maneuver Burr into the banking business to compete with the New York banking monopoly engineered by Hamilton and the Federalist Party.

Burr created the company in 1799 ostensibly to provide Manhattan residents with clean drinking water. The real purpose of the company, however, was to maneuver Burr into the banking business to compete with the New York banking monopoly engineered by Hamilton and the Federalist Party.

A loophole in the Manhattan Company’s charter allowed it to use excessive assets from the water business to make loans and sell shares. If Hamilton understood what Burr was up to, he undoubtedly would have tried to prevent it. But he didn’t notice the fine print. The Manhattan Company raised $2 million, invested $100,000 in water, and used the rest to start a bank. Banking was so profitable that the Manhattan Company sold the water business in 1808 and after that operated solely as a bank. After merging with Chase National Bank in 1955 to form the Chase Manhattan Bank, today it is part of JPMorgan Chase.

While I don’t know enough about either Trump’s or Burr’s businesses to comment on the merits of their actions, they have much more in common than just an address. Both were successful New Yorkers who sought and exercised national political power. And both were involved in contested elections: Burr in 1800, Trump in 2020.

The 1800 presidential election pitted Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican, against incumbent President John Adams, the Federalist candidate. Burr was also on the ballot as a Democratic-Republican. The Electoral College vote eliminated Adams, with Jefferson and Burr tied. As required by the Constitution, the election went to the House of Representatives to decide. Hamilton used his influence in the House to tilt the outcome to Jefferson; Burr, who became vice president, never forgave him.

Trump, like Burr in his day, has built his political base on an appeal to the “little guy.” Burr opposed Hamilton and his Federalist Party, which sought a strong, centralized government. Burr’s Manhattan Company provided banking services to shopkeepers, craftsmen and workers, his party’s base. Trump similarly appeals to working-class Americans who see “Washington” as out of touch. Two and a half centuries after Burr, Trump campaigns against “The Swamp.”

One of the core principles of America, as old as the country itself, is the concept of a free commercial society based on the voluntary exchange of goods, services and labor. Such a society can thrive only when the bodega owner in Florida, the bookstore empresario in Wisconsin, the manufacturer in the Carolinas, the vintner in California, and millions more like them, have confidence that their efforts, transactions and gains will enjoy the same legal and physical protections as the high and mighty, the prominent and powerful.

Of course, this doesn’t always work in practice. How do businesspeople react when the system fails them? In Burr’s and Trump’s cases, they tried to outwit their adversaries, trading a transactional system for its alternative, an honor society.

Conflict, under a code of honor, is resolved by the duel. In Burr’s day, duels sometimes ended in death. Today, they take place on social media or in court.

Like Aaron Burr before him, while arguing politically for a transactional society, Donald Trump ironically resorts to dueling when it suits his purpose. Burr’s legacy lives on at 40 Wall Street. Trump could still lose the building. But he has a strong record of winning duels.