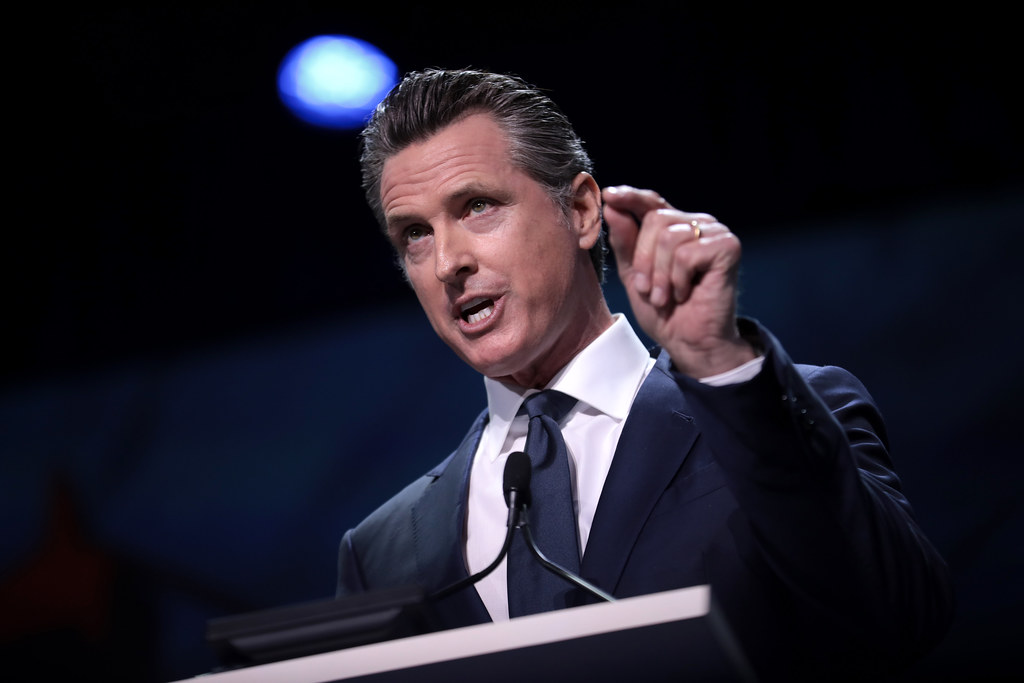

It is thought that California Gov. Gavin Newsom is considering a run for president. In many ways, the size and technological muscle of his state allow him to act like one already. California is home to 32 of the world’s top 50 AI companies, and AI startups investing in California broke records last year. When Newsom signs or vetoes legislation to regulate technologies like artificial intelligence, he affects everyone, and he knows it. That’s a lot of faith to put in a man whom the other 49 states never elected.

Imagine a world in which Newsom never decided to veto California’s infamous Safe and Secure Innovation for Frontier Artificial Intelligence Models Act, which would have required all AI developers, large and small, to certify — risking millions of dollars in penalties — that their models could not be used to “cause harm.” That near-miss reality asks developers to accept the risk of bankruptcy for actions outside of their control.

For many developers unwilling to take that risk, the law would have required them to keep tabs on their model’s uses, constantly reporting so-called “risky behavior” to the attorney general. Meanwhile, a new Board of Frontier Models would lead in rulemaking and enforcement, nested under the Government Operations Agency, a cabinet-level agency answering directly to the governor.

Each of these requirements is enough to overburden innovators and would have scared many from advancing this life-changing technology. Thankfully, after 20 days of deliberation, Newsom decided against it, not because of the chilling effect on industry but because it had no data to back its decisions.

In his veto letter, Newsom wrote that safety protocols must be adopted, but “I do not agree, however, that to keep the public safe, we must settle for a solution that is not informed by an empirical trajectory analysis of AI systems and capabilities.”

He went on to say the would-be law “does not take into account whether an AI system is deployed in high-risk environments, involves critical decision-making or the use of sensitive data,” highlighting several goals that later became hallmarks that other states included in their regulatory offerings.

California is signaling it will soon take another stab at larger, comprehensive AI regulation. It has passed 18 AI bills with smaller scopes, and the recent 52-page California Report on Frontier AI Policy delivered the needed empirical justification for regulation. Meanwhile, state Sen. Scott Wiener introduced a bill declaring the intent to make another bill. When California makes its next attempt, the rest of America may not be so lucky.

If companies have 50 states passing unique regulatory regimes, complying with the most restrictive one can equate to compliance with all. That means California’s heavy-handed framework would become a de facto national standard for everyone.

A similar effect exists in internet privacy. While these laws seem tailored to only California residents and businesses, estimates from the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation indicate that California’s privacy laws cost the rest of the country $32 billion annually, with $6 billion placed squarely on the shoulders of out-of-state small businesses. California’s compliance costs don’t stop at the border, and there is no reason to expect AI policy to be different.

Californians are not oblivious to this. In his veto statement, Newsom argued California has a role to play in crafting regulations with national security implications, “especially absent federal action by Congress.” Former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi chimed in, saying, “AI springs from California. We must have legislation that is a model for the nation and the world.” California’s outsized influence is understood.

Newsom’s pen reined in the worst example of extraterritorial AI regulating, for now. He may sign revised legislation if it adequately adds the new restrictions he seeks.

Congress must step in. It cannot cede national lawmaking to one governor, no matter how many AI firms are within his state borders. In the aftermath of the AI moratorium, House Energy and Commerce Chair Brett Guthrie, R-Ky., indicated that House Republicans will try freezing state-level enforcement again. This is a good first step, but Congress should get to work preparing its proposals.

Unless he makes a successful bid for the Oval Office, Newsom represents only the citizens of his state — not his neighbors, and indeed not the nation. Nevertheless, he has more power over AI than any other governor because the state he leads has the most outsized influence on the industry in the country. Congress, the representatives for the rest of us, must not abdicate its national lawmaking power. Decisions regarding the future of AI affect all of us.