The Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works (EPW) is holding a hearing Wednesday regarding controversial changes the EPA wants to make under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA).

The EPA wants to restrict — or even ban — the use of chemicals key to the manufacture of high-tech microchips, putting it at odds with the goals of the CHIPS Act, recently passed with bipartisan support by Congress.

Because it is “vital to our economy,” the Biden administration has promised $162 million to help the domestic microchip industry. However, the EPA is pushing drastic regulations on the production of chemicals like methylene chloride, perchloroethylene (PCE), and carbon tetrachloride (CTC) — all essential to producing those chips.

Supporters of the act tout the national security aspect of moving the production of chips that are vital to the U.S. economy and defense production. But there is another, more pragmatic consideration: the economy and jobs in the states where those new chips and the ingredients needed to produce them will be made.

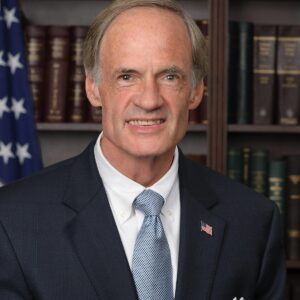

Nearly every Democratic senator on the EPW Committee has businesses that the EPA’s proposed rules will negatively impact. Of particular note is Delaware, home of EPW Chairman Tom Carper (D). He has bragged about “the state and federal government working together to push for further economic growth and make great things happen in Delaware.” But siding with the EPA could put him at odds with major businesses in his home state.

Delaware’s Chemours Company, for example, warned against the strict TSCA rules in a 13-page open letter, insisting that the EPA’s restrictions could disrupt supply chains, force reliance on foreign producers, and require alternatives that are much worse for the environment.

The DuPont Company in Wilmington, Del., also weighed in on the proposed rules, saying they would hurt business.

Delaware isn’t alone.

A $40 billion, taxpayer-subsidized chip-making plant (known as a “fab”) in Arizona — home of EPW Committee member Sen. Mark Kelly (D) — is useless if the chemicals needed to make the chips are either banned or become so costly that manufacturing is no longer realistic. That is the dilemma before the committee.

In Michigan, home of Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D), Dow Chemical warned the EPA that the chemicals it wants to ban are essential for cleaning tankers. If the tankers can’t be cleaned, it could disrupt trade routes in Lakes Michigan, Huron, and Erie that are vital to the Wolverine State’s economy.

And Pennsylvania-based polymer manufacturer Covestro told freshman Sen. John Fetterman (D) that if it can’t use these already well-regulated chemicals to produce its range of military products – like bulletproof glass and fighter jet canopies – Covestro will have to import them, keeping key parts of our defense supply chain offshore.

Pittsburgh’s Lanxess Corporation warned that the rule would prohibit domestic production of its flame retardants, forcing its customers to buy them from China, where no environmental regulations exist. The EPA would “devastate global supply chains while achieving no improvement in human safety and no new benefit to the environment,” Laxness told the committee.

Sens. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) and Ben Cardin (D-Md.) have also heard from concerned constituents who say Democrats in Congress should balance regulatory concerns with the broader goals of the CHIPS Act.

“Letting the EPA stop the creation of these new tech jobs, in a sector that our national security depends upon, is a losing issue for Democrats in swing states,” said former EPA spokesman Jahan Wilcox. “This is an example of the extremists in their party hurting them with average voters.”

Polls show only a third of voters approve of the job President Joe Biden has done handling the economy. Polls also show more Americans trust Republicans to do a good job on the economy than the Democrats.

How Congress handles the CHIPS Act and supports U.S. high-tech manufacturing could influence how Americans view the two parties in the future.