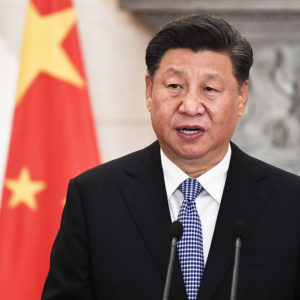

Much ink has been spilled analyzing Communist China’s National Party Congress in which dictator Xi Jinping unsurprisingly awarded himself an unprecedented (in recent times) third five-year term. Thus, not since the communist regime’s founder, Mao Zedong, had a Chinese leader amassed so much power.

However, breaking this precedent is not the most critical thing about Xi’s already long tenure (10 years as leader). What is more important is his diversion away from a partial market-oriented economic policy toward a re-emphasis on the socialism of China’s past. This move is bad news for the prosperity of China’s 1.4 billion people but good news for U.S. security.

Under Xi’s re-emphasis on favoring inefficient state-run corporations (the textbook definition of socialism), government preference for certain private firms, and party “guidance” for all private firms, the Chinese government’s intervention in the economy has significantly increased. In addition, in assembling the new ruling Politburo Standing Committee, which runs China, he chose all loyal political cronies with no visible economic expertise — thus stifling any dissent on economic policy or other policies.

Such strict repression of alternative ideas within that governing body and with party committee committees overseeing private companies will hurt China economically. Already, because of such increased state intervention in the economy, including the complete shutdown of major cities because of COVID, Chinese economic growth has plummeted.

Other handicaps to future Chinese growth are its rapidly aging citizenry and population imbalance, with many more men than women resulting from the Communist Party’s long-term one-child policy, which was finally dumped but still has long-term consequences.

With increased government meddling in the economy, China is unlikely to avoid the middle-income trap — wherein increases in wage rates of developing countries make them uncompetitive in labor-intensive industries (for example, China’s average wage rate is now about double that of Vietnam), and a failure exists to move from imitating technology of developed economies to genuine first-tier technological innovation.

The United States and the West have already closed off much of the high technology and talent for China to make this economic leap.

Yet such economic elevation would be needed to fulfill Xi’s focus on becoming a first-rate military power. China’s current military spending has increased to $300 billion per year, second only to the mammoth U.S. military budget of $800 billion yearly. Despite the spending gap between the two countries shrinking somewhat over past decades, the military capability accounted for by the gap is cumulative, thus rendering the Chinese a distant second to the United States in military potency.

And likely worse than the spending numbers is the reality. If Xi has any military understanding, the botched Russian invasion of Ukraine should trigger red-flashing warning lights for him. Before the disastrous move by Russian leader Vladimir Putin — also a dictator like Xi — the Russian military allegedly had been modernizing from its prior post-Soviet collapse and was supposed to be the second best in the world, next to the U.S. military.

However, as with the Soviet military before it, corruption was rampant — so much so that lots of modernization money apparently found its way into the pockets of generals and other high-level Russian government officials. Given the propensity of lower levels to shy away from giving bad news to repressive autocrats, Xi likely has to worry about whether he has been lied to about the potency of his modernized military, especially in the corrupt Chinese communist system that Xi knows all too well.

Furthermore, modernizing militaries in the developing world often get mesmerized by high-tech Western weapons to the detriment of investing in the “glue” that holds militaries together when they actually fight wars — for example, logistics, training, and command, control, and intelligence. Even Russia is now learning this common lesson, which usually only becomes apparent when the shooting starts — in other words, too late to fix it.

The Chinese military likely hasn’t learned this lesson either, as demonstrated by China’s imitation of the West in its building of vulnerable aircraft carriers.

The U.S. security agencies have been worried by Xi’s recent nationalistic threats against Taiwan — so much so that President Biden, on multiple occasions, has unwisely pledged to defend the island. Although his aides subsequently had to clean this up by saying that the intentionally ambiguous U.S. policy toward any Chinese attack on Taiwan still held, Biden has made it more difficult for him and future U.S. presidents, to avoid fulfilling his verbal commitment to Taiwan’s defense against a nuclear-armed great power. And Taiwan is a lot more important to China than it is to U.S. security.

In some ways, a Chinese amphibious invasion of Taiwan could be more difficult to pull off than the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Islands have natural moats of water around them, and amphibious assaults are one of the most difficult military operations to conduct successfully — especially with the element of surprise being harder to achieve with the advent of satellite and other airborne surveillance and improved coastal defenses of mines, diesel submarines and guided missiles.

For these reasons, the U.S. Marine Corps has not launched a large amphibious assault since the Korean War. Even a Chinese naval blockade around the island would expose Chinese surface warships to modern air attack — the potency of which was vividly demonstrated in World War II, in the Falklands War in the 1980s, and more recently with the Russian flagship Moskva being sent to the bottom by home-grown Ukrainian anti-ship missiles.

In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, instead of panicking about a Chinese attack on Taiwan and pledging to defend the island with U.S. forces, Biden would be better off replicating U.S. policy toward Ukraine since Russian sponsorship of a rebellion in eastern Ukraine in 2014. The United States helped Ukraine build an effective military the right way. Biden can assist Taiwan in advance by helping it develop a “porcupine strategy” — encouraging Taiwan to pay attention to the aforementioned military “glue” and to buy mines, anti-ship guided missiles, and even diesel submarines rather than higher tech Western military systems.

Rather than defeating a stronger foe, a porcupine strategy is designed to inflict enough damage to deter it from attacking in the first place.

The porcupine strategy should be even more viable if Xi, as seems likely, continues to handicap China’s economy and society, and thus its military, by accelerated state intervention in every aspect of Chinese life. In other words, the future Chinese military threat to U.S. security is likely to be as hollow as the one from Russia has proved to be.