Back before streaming films on Netflix, before TV or radio or records or movies—in fact, before any type of electronic entertainment—folks took pleasure in the simple things in life.

Like watching two steam locomotives crash in a head-on collision.

No, really, they did. Staged crashed were actually a thing. This is the story of one that went spectacularly bad.

In 1896, railroads had a problem. Their old 30-ton steam locomotives (some of which had been in service since the Civil War 30 years earlier) were being replaced with powerful new 60-ton models. That left them stuck with lots of worthless clunkers.

William Crush had an idea for getting rid of two of them.

That May, a railroad in Maryland had held one of the very first staged train collisions. And it was a great success.

Crush was an agent with the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad, which everyone called the Katy because of its initials. (As in the blues classic, “She Caught the Katy.”) He was always looking for ways to drum up new business. The rail line was looking to get rid of its old engines. His idea would kill two birds with one stone.

Crush envisioned an event that folks would talk about for years to come. Being a Texan, he imagined a collision that would be bigger, grander, louder than the one in Maryland. He pitched it to the Katy brass, who enthusiastically told him, “Go for it.”

A special stretch of track in East Texas was laid for the event. Each end was on a hilltop, with the smash-up coming down in a bowl area so there wouldn’t be a runaway train.

A giant tent was borrowed from the Ringling Circus. Two water wells were drilled. A grandstand was built along with telegraph offices, a stand for reporters, medicine shows, lemonade and cigar stands, and sideshows. “It’d be worth going just to see all that,” the construction foreman was overheard saying.

Organizers jokingly called the temporary spread “Crush, Texas,” after the man who originated it. And so the event had its name: The Crash at Crush.

Crush promoted it extensively. There was no admission charge. The Katy would make money from selling excursion tickets to folks who wanted to see the big event. It even offered a deal: $2 round-trip from anywhere in the Lone Star State.

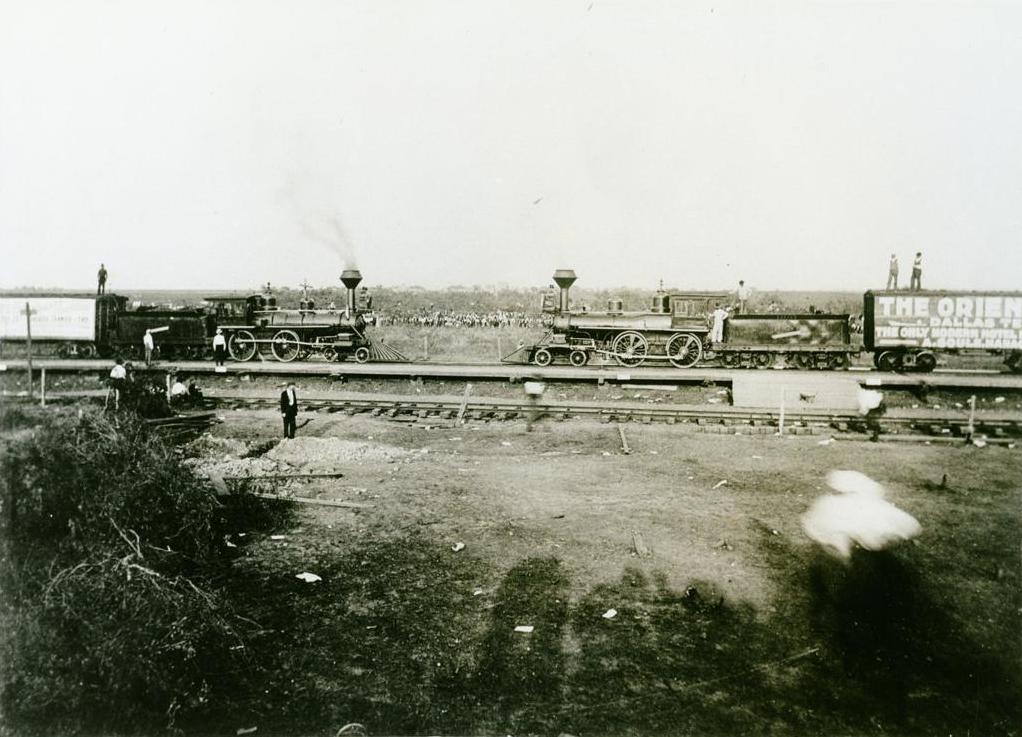

The big day finally arrived. On Sept. 15, 1896, Texans turned out in droves, an estimated 40,000 of them. It took 30 special trains to get them all there. They we placed on a hillside some 200 yards from the crash site for optimal viewing and safety.

That last point concerned Crush. But Katy officials assured him nothing could go wrong. The boilers were rupture resistant, and even if they did burst, it was unlikely there would be an explosion.

Excitement built as the scheduled time approached. The crowd resisted when police ordered them back, delaying the start by an hour. At 5:00 p.m., it finally began.

Like boxers climbing into the ring, the two steam engines (each pulling a few boxcars filled with railroad ties) met at the collision site and touched cowcatchers. Photographers popped away getting pictures. Then each engine backed up to its starting point. Crush, mounted on a white horse, gave the signal, and it was on.

The engineer in each cab stayed aboard for precisely four turns of the driving wheel, then opened the throttle wide and jumped. The trains rushed toward each other at around 50 mph.

Within seconds, they slammed into one another at full speed. And that was when everything went wrong.

First, there was a shower of splinters amid hissing steam. Then the very thing the experts had said wouldn’t happen did. Both boilers exploded, turning broken bits of metal into missiles heading straight toward the spectators. One news account said the size of the debris ranged from a postage stamp to an entire engine wheel.

Pandemonium erupted as thousands of people tried to flee. When the chaos finally calmed down, two people were dead. At least six others were seriously hurt, including a newspaper photographer who lost an eye.

Crush was fired the next day. But he was quickly rehired the day after that because of what happened next. Or more precisely, what didn’t happen.

There was no public outrage. The Crash as Crush was major national news for days. Folks couldn’t get enough reading about it. The accident actually boosted the Katy’s image, including carving out a name for itself in Europe for the first time. Scott Joplin even wrote a ragtime hit song called “The Great Crush Collision March.”

Americans simply shrugged off the tragedy as “It was just one of those things.” William Crush wound up spending six decades working for railroads. And incredibly, staged steam engine collisions remained popular attractions at fairs until the 1930s.