Folks in Tennessee disagree about many things. Are you a Vandy fan, or do you root for the Volunteers? Do you vote for Democrats or Republicans? Appalachian Bluegrass or Memphis Blues?

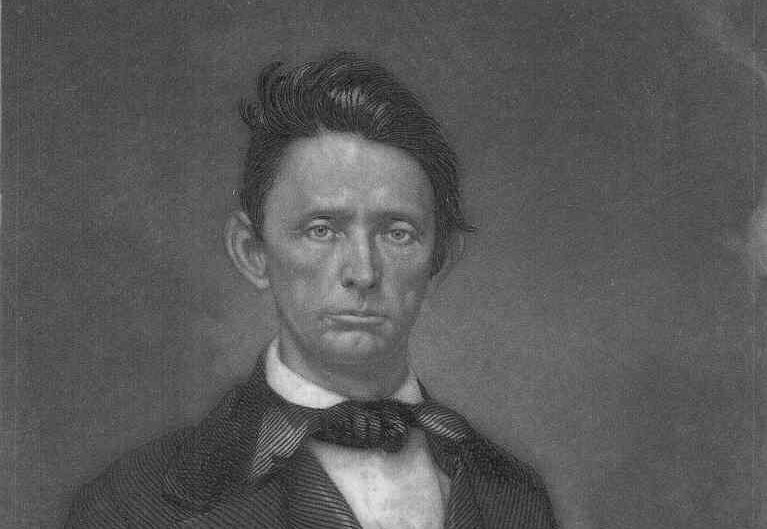

But they agree on one thing: Parson Brownlow is the most hated man in Volunteer State history. Nearly 150 years after his death, just mentioning his name can trigger a reaction.

Brownlow passionately hated (in no particular order) Baptists, the Devil, Democrats, Confederates, Andrew Johnson, and anyone who disagreed with him. And he fought them all with every ounce of energy he possessed.

How did this 19th-century Methodist minister, newspaper editor, politician, and all-around rabble rouser come to be a divisive figure in the 21st Century, you ask?

William Gannaway Brownlow was born in Virginia in 1805. Orphaned at age 10, he was bounced from one relative to another until becoming a carpenter at 18.

A couple of years later, he attended a camp meeting and had a spiritual conversion. He put down his hammer and saw, put on the cloth, and offered his services to the Methodist Church, acquiring the nickname he would carry for the rest of his life: “Parson.”

Brownlow lived in a world without shades of gray. People were either deepest black or virtuous white. There was no in between. And he charged into his ministry with a take-no-prisoners approach.

He was sent to churches in North Carolina, where he spent much of his time fighting with fellow Protestant ministers. When that didn’t work out, he was sent to South Carolina, where he published a 70-page pamphlet that attacked Baptists so viciously, the locals demanded he be hanged, making him beat a fast path back to Virginia.

With his fiery style, a friend suggested he start a newspaper in Tennessee supporting the Whig political party. Parson Brownlow plunged into it like a flamethrower going full blast. He was as divisive as ever: folks either loved or hated him, and he was perfectly happy to be treated either way. In 1840, he ran into a former Whig who had switched to the Democrats on a public street. They argued; Brownlow beat the guy with a cane, who in turn shot him in the thigh.

In 1845, he ran for Congress against former tailor and future President Andrew Johnson. It was every bit as nasty as you’d expect with the Democrat Johnson winning, sparking an intensely personal, burning hatred for Johnson, which Brownlow nurtured till the day he died.

Settling in Knoxville, there were more savage attacks on political and sectarian opponents of all stripes. He caused controversy in 1856 when he published a book in response to a Baptist minister’s attacks on Methodists. Eyebrows were raised because Brownlow’s book contained an illustration showing a Baptist man putting his clothes on in front of women following a rural creek baptism. (Gentlemen dressing in front of ladies was a huge no-no in mid-Victorian America.)

When the Civil War began, Tennessee joined the Confederacy. But Parson Brownlow did not. He was such an outspoken Unionist that Confederate leaders drove him out of Knoxville. In exile, he was paraded around the North as an example of a “good Southerner” who had stayed loyal to the Union. And he loved the limelight, too. A best-selling dime novel called “Parson Brownlow and the Unionists of East Tennessee” inspired a Philadelphia songwriter to compose a hit song titled “The Parson Brownlow Quickstep.”

In January 1865, a Unionist convention nominated him for governor, and he was easily elected (a big chunk of voters couldn’t cast a ballot because they’d been Confederates). He arrived in Nashville (a city he called a “dunghill”) and started his new job.

Gov. Brownlow ran his state with an iron fist. He made sure Tennessee was the first Southern state readmitted to the Union during Reconstruction, and that ex-Confederates were kept out of public life. He especially enjoyed going out of his way to make things difficult for everyone who’d worn the gray. He gleefully supported the Radical Republicans, whose top priority was making the presidency a living hell for Andrew Johnson. He was elected to the U.S. Senate and died soon after completing his term in 1877.

Parson Barlow was—and remains to this day—admired by some and despised by others. Even his official portrait played a role in his legacy.

Shortly before leaving the governor’s office, Brownlow commissioned a gigantic, eight-foot by six-foot painting of himself in all his glory and hung it in Tennessee’s Capitol. His opponents were outraged.

For decades, they spat on it as they passed, drenching it in dark brown tobacco stains. It eventually became such an eyesore, it was quietly removed from public display.

In the 1980s, someone decided it was time to restore Parson Brownlow to the State House walls. An eruption of public outrage followed, dominating talk radio and newspaper editorials.

Finally, the legislature voted in 1987 to permanently ban the portrait from the very Capitol building where Brownlow had served 130 years earlier. It was quietly relocated to the Tennessee State Museum.

Even Brownlow’s final resting place isn’t safe. Police still get reports from time to time of attempts to desecrate his grave in Knoxville’s Old Gray Cemetery, efforts to avenge injustice suffered by vandals’ ancestors.

All this for a man who died in 1877.