One day in June 1921, the editor of the Herald newspaper in Troy, Ala., finally had enough. A clipping from the previous Sunday’s Brooklyn Daily Eagle lay on his desk. “An Assassin’s Monument,” the headline said. It had been reprinted in papers nationally.

The editor angrily banged out his reply on a typewriter. “The people of our city do not appreciate the publicity we are getting out of this thing,” he fumed.

You couldn’t blame them. After all, for 15 years, the tiny town of Troy had been stuck with a notoriety not of its own making.

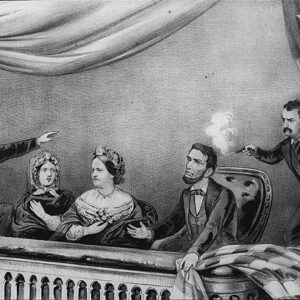

It was home to the only monument honoring a presidential assassin. And not just any president-killer, either, but the most despised villain of them all: John Wilkes Booth.

Blame it on Pink Parker.

It’s important to understand at the outset that Pink wasn’t a backwoods redneck. He was educated, a law officer, a devout Christian, a loving husband and father, a man well-liked by his neighbors.

With one huge exception. He had a burning hatred of Abraham Lincoln that grew into a psychotic obsession. Because he simply was unable to let go of the terrible things that had happened to his family.

His story began quietly enough. Joseph Pinkney Parker was born into a respectable family in Coffee County, Ala., in 1839. He had just finished his education when the Civil War broke out. Pink put on a gray uniform and marched off with the Confederate Army.

Returning home in 1865, he was trapped in the nightmare that was Reconstruction. The family farm was overrun by weeds, livestock gone, personal property stolen, his sister deeply embittered by the treatment she had received from Union soldiers. The county soon took his home for unpaid taxes.

He tried being a schoolteacher but gave it up when his pupils’ parents couldn’t pay him. He got a job as a railroad “walker” carrying a sledgehammer and bag of iron spikes to keep rails in order. It was grueling, exhausting, low-paying work.

Pink Parker married and started a family. (Relatives remembered he never called his wife anything but “Darling.”) He was a dedicated Baptist, became a police officer, and eventually built a comfortable home in Troy.

But somewhere in his heart was a hurt too painful to heal, a cut so deep no scar could ever cover it.

Pink Parker simply never got over what the Yankees had done to his home, family, and future. And in his mind, the blame lay entirely at one man’s feet: Abraham Lincoln.

This otherwise friendly, likable man would erupt in a volcano of hatred whenever Lincoln’s name was mentioned. In fact, the only time he ever swore was when he heard Lincoln’s name, and the torrent of obscenity was so profane he was eventually kicked out of the Baptist Church because of it.

His family and neighbors tried to overlook this single glaring flaw. But that grew harder and harder to do.

Then he devised a scheme in 1906. He would put up a marker honoring the man who took Lincoln’s life—assassin John Wilkes Booth.

The people of Troy were horrified one day when Pink displayed a four-foot-tall stone marker inscribed, “Erected by PINK PARKER in honor of John Wilks (sic) Booth for killing Old Abe Lincoln.”

Pink offered to erect it on the courthouse lawn or in a city park. But nobody touched it with the proverbial 10-foot pole.

So, Pink put it in his front yard. He even sent a postcard to President Theodore Roosevelt, inviting him to come and see the monument for himself. (The White House never replied.)

With Pink’s house in a quiet residential neighborhood, few people saw the marker. Every so often, a newspaper reporter from a Northern state would write a story about it, causing great mortification to the people of Troy. But it had been bought with private money and placed on private property, so there wasn’t much they could do about it.

By 1921, Lincoln had been dead for 56 years. To many people, the Civil War seemed as remote as the Vietnam War seems today. Pink was 82 then, nearly blind, and in rapidly failing health. Boys tipped over the monument as a Halloween prank. Pink’s family didn’t put it back up.

It was still lying in the dirt when he died that December.

His sons hauled the monument to the local stone carver. The writing was wiped away, replaced by Pink’s name and birth and death dates. What had started as a tribute to a murderer was turned into his tombstone.

And so it stands today in Oakwood Cemetery, tilting to one side like the leaning Tower of Pisa. No trace remains of the words that once reminded the world of Pink Parker’s inability to forgive and forget, to heal and move on.