Was the most famous moniker to come out of the Civil War actually a bit of misplaced snark?

When Thomas Jonathan Jackson was at West Point, his classmates (and the cadets he later taught at Virginia Military Institute) called him “Old Jack.” And so he was known … until a blazing hot Sunday afternoon in late July 1861. The Battle of Manassas (or Bull Run to the Yankees), the war’s first major engagement, was underway in northern Virginia near Washington. Jackson was there as colonel of the 1st Virginia Brigade.

Things were going badly for the Southerners. They kept getting pushed back by the boys in blue. South Carolina Confederate Gen. Bernard Bee pointed to Jackson’s men and said, “There stands Jackson like a stone wall.” From that moment on, the man was Stonewall Jackson, and the military unit was the Stonewall Brigade.

But here’s the mystery: Was Bee being complimentary or sarcastic? He had been trying to persuade Jackson to attack, which the Virginian refused to do. Some historians, plus Bee’s adjutant who was there, claim the phrase “stands like a stone wall” was a snide putdown, not praise for Jackson’s grim resistance.

We’ll never know the true meaning of Bee’s words because he was wounded soon after speaking them and died a few days later. His precise intention went to the grave with him. (Jackson followed 22 months later.)

And if the Union Army had a party boy, it was Joe Hooker. Sandy-haired and blue-eyed, he knew how to have a good time. Perhaps, some said, too good. One prudish Bostonian smugly wrote Hooker’s headquarters was “a place where no self-respecting gentleman liked to go, and no decent lady could go.”

He sent a report on the 1862 Battle of Williamsburg, Va., to the brass in Washington signed “I am still fighting — Joe Hooker.” But the message was garbled in transmission. The dash got lost. It came out, “I am still Fighting Joe Hooker.” Newspaper reporters, then as now eager for a new angle to a story, seized on it. A nickname was born.

Hooker was an aggressive fighter with a great love of the spotlight. But ironically, this publicity hound hated the name pinned on him. He said “Fighting Joe” made him sound reckless, stupid or, worst of all, “like a common bandit.” Like it or not, the nickname stuck — even after his embarrassing defeat to Gen. Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville.

There’s a widely repeated but utterly false story that Hooker’s name itself became a nickname for prostitutes. Many people claim the term “hooker” was inspired by Joe Hooker’s frequent patronage of them. Not true. “Hooker,” used in connection with practitioners of the world’s oldest profession, appeared in print well before “Fighting Joe” rose to fame in the Civil War. However, the general did turn a blind eye to army regulations and allowed prostitutes to follow the army, claiming it was good for morale. Those women were nicknamed “Hooker’s Division,” and that certainly helped popularize the term. So indirectly, Joe Hooker was associated with “hookers.”

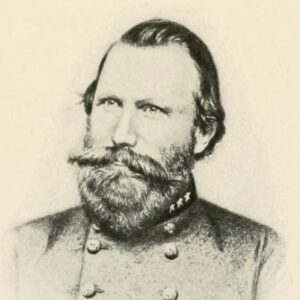

And then there was James Ewell Brown Stuart. As a boy, he created a new name from the first initials of his first three names: Jeb. And people called him that. But some of them called him something less flattering, too.

Stuart had a soft, weak chin that gave his face an almost feminine quality. A classmate said the chin was “so short and retiring as positively to disfigure his otherwise fine countenance.” The guys had no trouble coming up with this snarky nickname: “Beauty.”

Stuart responded the only way he could. He grew a beard immediately after graduating from mandatorily required clean-shaven West Point. A fellow officer said Stuart was “the only man he ever saw that (a) beard improved.”

The weak chin was hidden from view, but the nickname “Beauty” stayed with him. In a way, Stuart got the last laugh. The beard he sported the rest of his short life was long, red, and wavy. It, coupled with his reputation as a dashing cavalryman and the ostrich plume he jauntily wore in his hat, made him attractive to the fair sex. Stuart was an unapologetic ladies’ man who loved basking in their attention.

And there you have it. Three nicknames still echoing across the battlefields 160 years later.