Americans were in shock in early July 1876. It wasn’t supposed to have been that way. It was the country’s centennial, after all, a time for a national party.

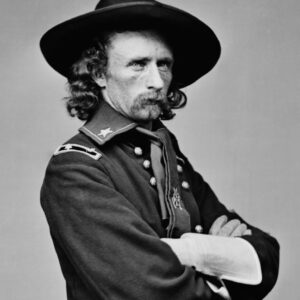

Instead, stunning news came from the distant Black Hills in Montana Territory. George Armstrong Custer, dashing Civil War hero and flamboyant Indian fighter, plus all 267 of his men, had been wiped out in a ferocious battle with Native American braves.

It had been a remarkable ride for Custer up to then. He became the union’s youngest general at 23 and caught the public’s fancy through glowing newspaper accounts of his bravery, his long curly hair (which he scented with cinnamon oil), and even his wartime wedding to a beautiful bride.

But the post-war years hadn’t been kind. His commission as major general was a brevet promotion, valid only as long as the Civil War lasted. When the ink dried at Appomattox, the man many people still call “General Custer” dropped three slots to the rank he held the day he died: lieutenant colonel. He was twice court-martialed, and although he beat the rap both times, his shining star was tarnished.

To regain its former luster, Custer knew he needed a big win on the battlefield.

But this time, the once “Boy General” who had survived having 11 horses shot out from under him and was lionized for his celebrated “Custer Luck” pushed his luck too far.

His story ended at age 36 on the last Sunday in June 1876 with his incredibly bad decision to attack an Indian village without properly scouting it first. (He rode straight into one of the largest Native American war camps ever assembled and was outnumbered 4 to 1.)

Yet, few people remember the Custer family lost much more than George that day. His two younger brothers, a brother-in-law and a nephew all died with him. Eclipsed by George’s fame, their stories are worth recalling.

Like many high–ranking officers then, Custer surrounded himself with an adoring, devoted circle of relatives. Folks called them the Custer Clan. They served together, traveled together and partied together. Their fortunes rose with George’s fortunes and declined with his. Come what may, they were in it together and would remain that way right up to the bitter end.

There was Tom, 31, the kid brother eager to win big brother’s approval. If George Armstrong (known in this intimate circle by the nickname “Autie,” his childhood mispronunciation of his middle name) hadn’t made the Custers famous, Tom would have. During the Civil War, he received the Medal of Honor not once but twice, becoming the first of only 16 men to ever gain that distinction.

At the Little Bighorn, some historians speculate Tom shot gravely wounded George to spare him from being tortured as a captive. Tom’s body was found nearby, riddled with arrows.

There was Boston Custer, 27, George’s beloved youngest brother. Too young and physically weak to serve in the Civil War, “Bos” viewed his elder brothers with hero worship. Eager to sip from the Custer cup of glory, he tagged along with the 7th Cavalry Regiment as a civilian contractor. Assigned to a different detachment, when a message arrived at the battle’s outset urgently calling for ammunition, Bos dashed off to his brothers’ side, galloping straight to his grave. (Ironically, had he stayed where he was, he would have survived.)

First Lt. James Calhoun, 30, was the Custers’ brother-in-law. “Jimmi” was a charter member of the Custer Clan, as was his own brother-in-law Miles Moylan, who was also in a different part of the Battle of Little Bighorn and survived, receiving the Medal of Honor himself the next year.

Finally, Henry “Autie” Reed, 18, was Custer’s favorite nephew. His mother gave him his uncle’s nickname, and there was a close bond between the two. Autie had been hired by the 7th Cavalry as a civilian beef herder. Volunteering his services for the Black Hills Expedition, his uncles accepted. When the battle began, Autie’s boss told him to stay behind with the supply wagons where he belonged. Autie simply grinned and shouted, “You’re just mad because you can’t go!” as he rode off into history.

When the smoke had cleared, five family members lay dead, the Custer Clan forever vanished. Admired by some and loathed by others, their legacy endures to this day. They teach us a fundamentally American lesson: If you must lose, go down with everyone fighting to the last bullet.

They were in life, and remain in death, the very embodiment of Shakespeare’s famous words in Henry V:

“From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remembered-

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers …”