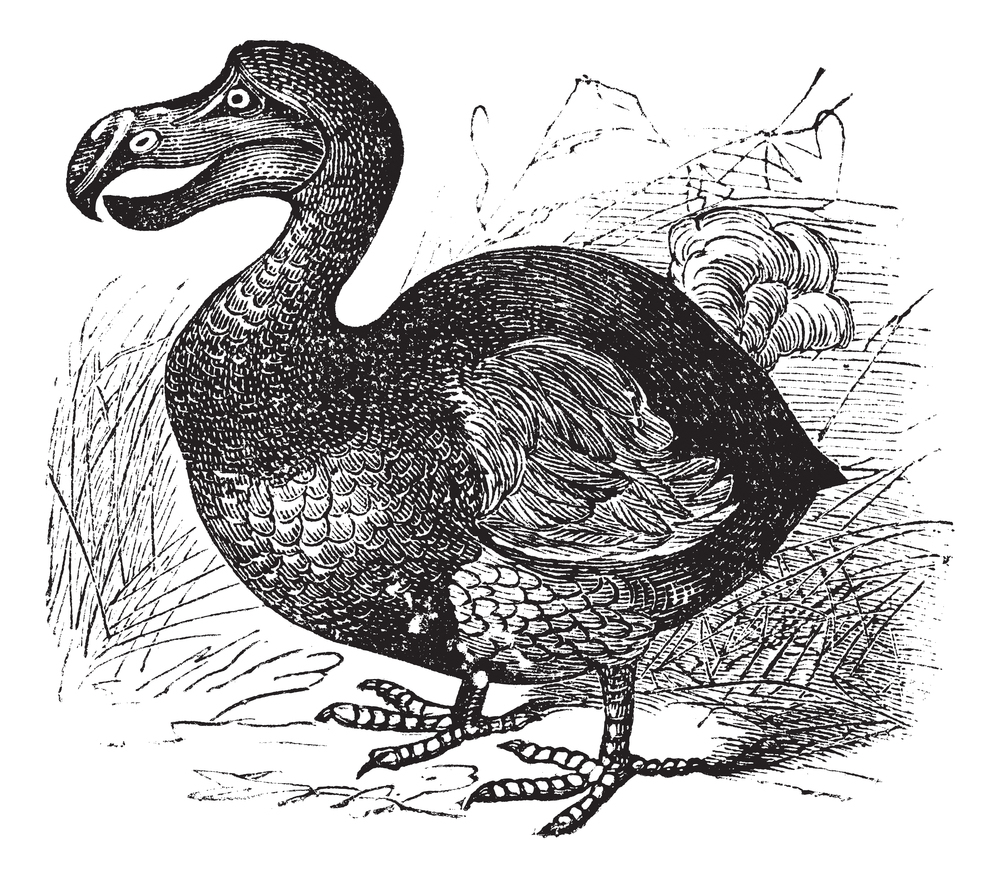

The extinct dodo bird was said to be unintelligent and clumsy. Contrary to popular belief, the creature’s disappearance had little to do with brain function or muscle power and a lot to do with human activity. Now, scientific breakthroughs are providing an opportunity to rectify our blunders.

Efforts to de-extinct the dodo bird are underway. Conservationists and scientists not only can but should follow through. Humanity has a moral responsibility to right our wrongs when possible.

Before extinction, the dodo bird’s home was a sub-tropical island off the east coast of Madagascar called Mauritius. Isolated from the rest of the world, its plants and animals thrived without outside interference. In the late 1500s, Dutch settlers landed on the island, triggering a chain of events that contributed to the dodo bird’s demise. They had been preceded by visits from other seafaring nations, which may have driven the first nails in the coffin of the dodo.

With the settlers came the introduction of invasive species like goats and deer, and worse, dogs, pigs, rats and cats — animals that had an appetite for the bird’s eggs or chicks. Given that dodo females have laid only one egg yearly in a nest on the ground, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to predict what happened. Fast-forward to the close of the 17th century, and the flightless bird was no more.

Now, conservationists and scientists are joining forces to help restore and maintain the island’s ecosystem. It supports animals that cannot be found anywhere else. Species include the vibrantly colored forest day gecko, echo parakeet, or endearing “flying fox,” with another neighbor moving in soon.

Advances in bioscience have granted scientists — in coordination with animal ethicists and practitioners — the ability to resurrect animals that have gone the way of the dinosaurs. While the creatures won’t be perfect clones of the original, the engineered species could look and act like the real thing. This may sound like science fiction, but the technology is on our doorstep.

The process all starts in a lab where scientists have been busy mapping the dodo bird’s genome. The DNA is being reconstructed using genetic material plucked from a dodo skeleton at the Natural History Museum of Denmark. From there, the next step is to blend the DNA with a genetic-living relative, the Nicobar Pigeon, and its closest and, sadly, extinct relative, the Solitaire from Rodrigues (an island close to Mauritius), to give birth to a living, breathing animal.

To prepare for the bird’s arrival, the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation — in partnership with Colossal Biosciences — is working to soften the proverbial nest. The foundation is removing invasive species from the island, restoring vegetation, and educating residents so the dodo can successfully be rewilded into its native habitat.

Restoring biodiversity within an ecosystem — rewilding — is a growingly popular conservation tool deployed in places from Africa to North America. The approach is limited to working with existing animal populations. Projects around white rhinos or wolverines are prime examples.

For extinct species, the Mauritian Wildlife Foundation has pioneered the use of proxy species, or living species close to extinct species, that can fulfill ecological niches and roles. For example, the foundation is successfully introducing the Aldabra Giant Tortoises to replace extinct Mauritian and Rodriguan endemic giant tortoises. Adding de-extinction into the strategy can take it a step further.

The dodo bird’s extinction is a sad illustration of human activity disturbing the natural world. Although sometimes unavoidable, we have the responsibility to reverse our mistakes when given the opportunity. If successful, the phrase “gone the way of the dodo” could soon be obsolete.