President Trump keeps proving his critics wrong, especially when it comes to his trade policy.

When he announced his “Liberation Day” tariffs in April, investors panicked and the stock market sold off 20 percent in a matter of weeks. Economists predicted soaring inflation and an imminent recession. Foreign policy analysts scoffed at the president’s pledge to negotiate better deals with trading partners.

None of that doom and gloom has come to pass. Stocks are at all-time highs. Recent inflation reports have been muted. Prediction markets put the chance of a recession in 2025 at just 11 percent, the lowest of the year. And the administration has now inked trade agreements with the European Union, United Kingdom, Japan, South Korea, and several other significant trading partners, deals that commentators across the political spectrum have characterized as lopsided in America’s favor.

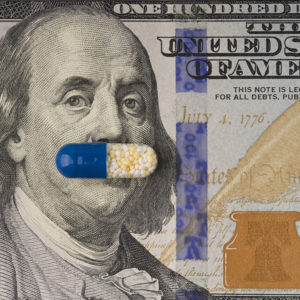

Therefore, it would be easy for U.S. officials to reflexively dismiss criticism of the Section 232 tariffs that they continue to suggest will soon be imposed on imported drugs. After all, critics previously warned about shortages, supply chain snafus, and soaring costs when the administration announced its other tariffs. Those fears proved unfounded.

As a trade negotiator in Trump’s first term, I’d urge my friends and colleagues in the second administration not to dismiss these warnings out of hand.

Pharmaceuticals differ significantly from other imported products. That’s why the predictions of shortages and soaring prices that previously proved false could prove true when it comes to our medicine supply.

Section 232 tariffs are effective tools to address national security threats. Trump has already imposed them on steel and aluminum, two metals that are essential for a range of military applications and other critical applications that drive our economy.

In recent decades, China has come to dominate the global steel industry, producing more steel than the rest of the world combined, and exporting its massive government-subsidized excess capacity at artificially low prices. Other countries also target the open and attractive U.S. market with enormous volumes of low-priced steel from their bloated industries.

Without tariffs, our domestic steel and aluminum producers would be unable to compete against the worldwide onslaught of products flooding in at rock-bottom prices. Doing nothing, as critics wanted, would have further hollowed out our steel and aluminum industries, leaving us dangerously dependent on other countries for products crucial to our economic well-being and unprepared for future conflicts.

Pharmaceuticals have obvious national security implications. China produces far too large a share of our generic antibiotics. Targeted Section 232 tariffs could compel drug companies to cut the communist-controlled nation out of their supply chains.

Extending those tariffs to brand-name drugs from allies such as South Korea, Japan, Switzerland and Britain could easily backfire.

Brand-name medicines aren’t commodity products. They are, by definition, unique products. If a doctor prescribes a patient a particular medicine, the patient needs that specific drug, not a different treatment for a different condition.

Because brand-name drugs are under patent protection, American firms legally can’t fill the void and produce copies of therapies made exclusively in Japan or Switzerland.

Of course, the hope is that high tariffs will eventually pressure companies to relocate production to the United States. Even if companies choose to expand their U.S. presence — and there are plenty of economic and political factors that could prevent them from doing so — building a pharmaceutical plant can take several years and cost well more than $1 billion.

Meantime, there’s a risk of higher drug prices or even shortages at pharmacies and hospitals if it becomes financially unviable for insurers and wholesalers to continue importing certain medicines.

Ultimately, the price will be paid by American patients, either directly in the form of higher pharmacy bills or indirectly in the form of worse health outcomes stemming from drug shortages and a decline in research and development investment.

The administration exempted EU-member states from any coming Section 232 pharmaceutical tariffs in the recent trade deal. It would be wise to exempt allies such as Japan, South Korea, Switzerland and Britain, and focus squarely on the threat from countries such as China.