The book of Ecclesiastes teaches that there is nothing new under the sun. So, it is with today’s banking and credit market crisis triggered by Silicon Valley Bank’s recent collapse. As in the past, years of excessive credit market expansion are now followed by acute financial sector problems and an incipient credit crunch. That hardly bodes well for the Federal Reserve’s hopes of avoiding a hard economic landing as it aggressively raises interest rates to regain inflation control.

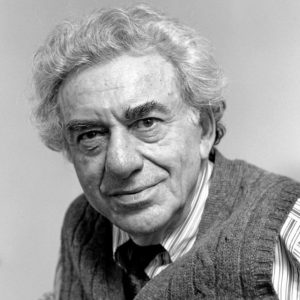

Hyman Minsky, the late American credit cycle expert, taught us that a prolonged period of financial-market stability tends to set up the conditions for pronounced financial market instability. By this, he meant that as economic confidence rises when money is easy, the financial system tends to make increasingly risky loans assuming that credit market conditions will remain easy forever. When credit market conditions inevitably tighten and asset prices fall, lenders realize that they might not get repaid. That, in turn, causes the credit-market house of cards to collapse, producing a recession.

The Fed’s excessively accommodative monetary policy response to the 2020 COVID economic recession makes it all too likely that today’s credit market cycle will be more severe.

The Fed juiced up financial markets by keeping interest rates low for too long and allowing the broad money supply to increase by a record cumulative 40 percent in 2020 and 2021. The Fed also flooded the market with liquidity through its aggressive bond-buying activity. Whereas it took the Ben Bernanke Fed six years to increase the size of the Fed’s balance sheet by $4 trillion after the 2008-2009 Great Economic Recession, in 2020, it took the Jerome Powell Fed barely nine months to do the same thing.

The net result of the Fed’s monetary policy largesse was creating a world “everything” asset and credit market bubble. Equity and home prices reached nosebleed levels. At the same time, credit flowed at unusually low-interest rates to borrowers with the dubious ability to repay. Those borrowers included highly leveraged companies, deadbeat emerging market countries hit hard by Russian-induced rising energy and food costs, and highly indebted Eurozone countries like Italy.

Making a hard economic landing all the more likely is that the Fed has been forced to slam on the monetary policy brakes to regain inflation control. Over the past year, it has raised interest rates by almost 5 percent, or at the fastest pace in more than 40 years. At the same time, it has shifted from a policy of flooding the market with liquidity through an aggressive bond-buying program to draining $95 billion a month in liquidity by not rolling over its bond portfolio at maturity.

The Fed’s shift from an ultra-easy monetary policy to one of abrupt tightening has caught off guard financial markets that had been lulled into believing that low- interest rates would last forever. Last year, the equity and bond markets suffered their worst year in decades. Troubling cracks have emerged this year in the U.S. and world banking systems. This is underlined by the recent Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank collapses at home and by the shotgun marriage of Credit Suisse and UBS abroad.

The September 2008 Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, which triggered the Great Economic Recession, was preceded by several credit events. These included the blowing up of a few hedge funds in 2007 and the Bear Stearns collapse in March 2008.

Fast forward to today, and there is no shortage of warning signs that real financial market trouble lies ahead in a world that has never been as indebted as it is. In addition to last year’s poor equity and bond market performance and the recent regional bank troubles, we have seen the collapse of cryptocurrency lending platforms, the need for the Bank of England to bail out the United Kingdom’s pension system and the default of some large Chinese property developers.

In September 2008, the Fed was caught flat-footed by the Lehman bankruptcy. With all the warning signs now flashing red, it would be inexcusable if the Fed is again caught in that situation later this year by a crisis in the banks or the equity and hedge funds.