In a month dedicated to the virtues of voter registration, it’s worth noting the success of voter ID, one of the few areas where the data and public opinion firmly align.

State and local election officials nationwide are promoting National Voter Registration Month in September, established in 2002 by the National Association of Secretaries of State.

As noted in my book, “The Myth of Voter Suppression: The Left’s Assault on Clean Elections,” polls consistently show that about 60 percent of Democrats, about 70 percent of non-White voters support voter ID, and about 80 percent overall support voter ID.

It’s only controversial among some in the political class, including President Biden, and certain special-interest groups such as the Brennan Center for Justice, the ACLU, and Stacey Abrams’ organization, Fair Fight Action.

These opponents contend ID requirements, or practically any other election integrity law, are a barrier to voting. Even though credible research shows ID doesn’t deter turnout, it is, in fact, a barrier to voting. So is voter registration itself. These are minor inconveniences that civil society has determined are accepted to ensure a modicum of election security.

Zero barriers to voting would mean freely allowing anyone to vote at any precinct and no means of tracking the voter’s locality or how many times someone voted. No one openly advocates this. But it’s difficult to see the logic behind characterizing voter ID for in-person and mail-in voting as voter-suppression while giving registration a pass.

For that matter, many of the same arguments used against ID laws today were used against adopting the secret ballot in the late 1800s. Voice voting or dropping a color-coded party ballot in a clear glass bowl was the norm in American voting until 1888.

When New York Gov. David Hill vetoed a secret ballot bill, he said the reform would restrict voters and would be advantageous to certain candidates. Other critics included the big-city political machines that claimed —for self-serving reasons — that forcing people to vote alone behind a curtain would disenfranchise what was at the time a sizable illiterate population.

Unlike voter ID laws, secret ballot laws meant an initial drag on turnout. But numbers soon climbed. Hill eventually yielded and signed a secret ballot measure for the Empire State.

Earlier this year, a study by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences was the latest to refute the claim that ID laws suppress voting. The study explored the effect of the laws on candidates from 2003 through 2020. The earliest voter ID laws “produced a Democratic advantage, which weakened to near zero after 2012,” according to the study. Such laws today have “negligible average effects” on who wins and loses, the study found.

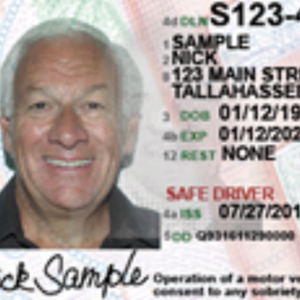

And there’s no reason the laws would change the result short of preventing fraud that would favor one candidate over another. Most Americans have some form of government-issued ID.

Voter ID laws can stop multiple types of fraud such as impersonating another registered voter, preventing non-citizens from voting, and stopping out-of-state residents or someone registered in multiple jurisdictions.

This is why in 2005, the bipartisan election reform commission co-chaired by former president Jimmy Carter and former secretary of state James Baker called for voter ID cards nationally.

A National Bureau of Economic Research study from 2019 examined 10 years’ worth of turnout data from across the country and concluded that voter ID laws have “no negative effect on registration or turnout overall or for any specific group defined by race, gender, age or party affiliation.” The NBER study found that voter ID laws don’t decrease voter turnout, including that of minority voters.

However, the study also determined ID laws have “no significant effect” on preventing fraud. But prevention-based laws could be based on proving a negative.

The one notable exception in research came in a January 2017 study from professors at the University of California San Diego and Bucknell University. That study claimed ID laws “diminish the participation of Democrats and those on the left while doing little to deter the vote of Republicans and those on the right.”

Those findings didn’t last long, as professors from Yale, Stanford and the University of Pennsylvania examined the same data and determined the original study had measurement errors and misinterpreted data. The Yale-Stanford-Pennsylvania study found there is “no definitive relationship between strict voter ID laws and turnout.”

Expanding voter ID laws to mail-in ballots was at the core of the more than 20 election integrity reform laws that passed in 2021.

Despite the partisan slanderous comments about the measures, such as “Jim Crow 2.0,” the evidence aligns with public opinion for the bipartisan support among Americans.